Volume Versus Intensity

Today I want to talk about a very interesting article from Aussie coach Alan Couzens, who asks the question 'Are you a volume or intensity responder?' This is certainly something I've been longing to know the answer to. If you're in the same boat, read on!

It's well worthwhile to read through the linked article, but I'm going to summarize the main points here.

Most cyclists with a power meter are familiar with the concept of Training Stress Score (TSS). This is an attempt to correlate training load with changes in fitness, and was itself developed based on the earlier heart rate-based TRaining IMPulse model.

Every ride is assigned a TSS, based on its intensity (fraction of FTP) and duration. Quite simply, the longer and harder you ride, the higher the training load (TSS), and the higher the training load the higher your fitness should become. High training loads also lead to high fatigue levels and the potential for overreaching and injury if you increase loads too quickly or beyond levels you can tolerate; the key to effective training is to balance optimal load with recovery.

The problem with the TSS concept is that it tries to track fitness via a single one-size-fits-all number. The way it's calculated means you can get a TSS score of 100 in many different ways. Three examples: riding for 60 minutes at FTP; riding for 60 minutes doing 30 second sprints at 250% FTP every few minutes with easy recovery in between; or riding for 4 hours at 50% FTP.

Anyone who's done these workouts knows that each has very different physiological effects, so clearly they're not interchangeable.

Each of us has a different natural ability and response to training. Some of this is down to genetics, which has a large effect on body type, cardiovascular capacity, muscle typology etc. So it stands to reason that we'll all respond differently to different methods of training.

In the linked article, Couzens discusses two of his athletes, both of whom are fast — winners of major endurance events — but each responds very differently to training. One of them thrives on 25-hour weeks of long slow distance, with low average intensity. He's a 'volume responder': the more he rides, the fitter he gets, almost regardless of how hard his riding is. The other is an 'intensity responder', who does much better on lower volumes at a much higher average intensity: he does a lot of high-intensity interval training and fewer endurance miles.

If we want to optimize our training, it would clearly be beneficial to us to be able to find out if we fall into one of these categories, or if a more balanced approach would suit us better.

The first step in doing this is to move beyond TSS, by separating out the two main terms in the training load equation: volume and intensity.

Couzens shows how to do this using your power and heart rate data. You look at each of your training blocks and get the totals for volume (hours ridden) and intensity (TSS per hour). You also have to calculate your relative VO2 capacity, which requires an extended maximal effort at the end of every block.

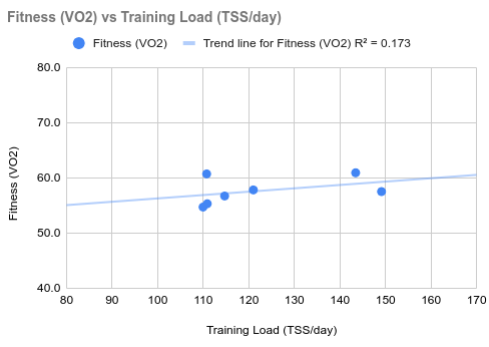

Once you've got this information, the first thing to do is plot VO2max score versus training load (TSS per day). This gives an idea of how fitness responds to just the raw TSS numbers, with volume and intensity not separated. Mine are shown below.

I took the liberty of adding in r2 values for each of these graphs, to judge the strength of the relationships plotted. As you can see, for me there is only a very weak correlation between my training load and fitness; it appears that a higher TSS is probably beneficial, but the effect is rather underwhelming. You can see that there were a couple of blocks in which I had a much higher training load than in the others, but considering the extra effort involved, this didn't make a great deal of difference.

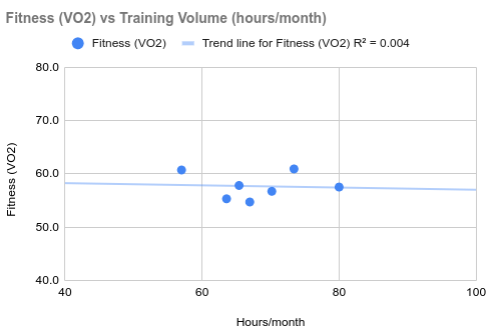

Hopefully we can get more insight by separating out volume and intensity. First, fitness versus training volume:

Ouch! Not only does increasing volume not help, if anything there's an inverse relationship: the more I ride, the worse I get! I'm not taking that too seriously, though, since the r2 value is so tiny (you can see the data points are all over the place, and don't cluster tightly around the line of best fit, especially given a big outlier on the left that's skewing things).

What it does mean is that, at least in the range of the data (about 13-18 hours riding per week), extra volume doesn't do much for me: I may as well ride at the bottom end of the range so I can save some energy and recover faster.

At this point all my cycling buddies who've been trying to get me to ride less over the last couple of years are laughing their asses off at me. Still, there is one way that higher volume helps: calorie burning. I'm currently on a weight loss program, and due to the way VO2max is calculated (the body's oxygen consumption, in millilitres per kilogram body weight per minute), any loss in body weight does actually improve relative fitness. And clearly, the more miles I rack up the easier it is to lose weight.

Furthermore, one important long-term factor in fitness improvement is cycling economy. This increases very slowly over many years, and the biggest factor in its development is total hours ridden. So maybe that's another reason to ride more, but not if it's at the expense of other aspects of my training.

Other than that, there's no reason for me to ride more than (at most) the low end of the volume range I've been riding at. Okay, great. Let's move on and look at fitness versus training intensity.

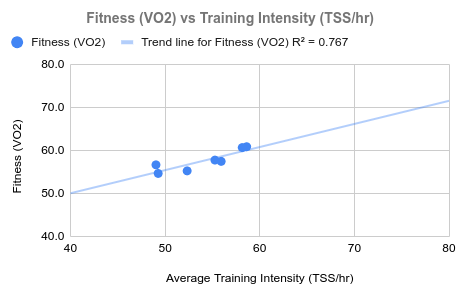

Now we get to the good stuff: a tight cluster of data points with a good strong correlation (r2 = 77%), and, even better, it's pointing in the right direction!

This is a nice steep line, and needless to say it's given me all kinds of ideas about how to experiment with my training over the next few months. Lately I haven't really been enjoying my very long rides, and now I don't have to think twice about reducing their frequency, while I instead shift my focus onto intensifying my training.

The first thing I'd like to see is a wider range of values on the X-axis: I need to do some blocks with an average intensity score in the 60s to see what happens. I don't want to extrapolate too far, but I'm optimistic that if I do this (and get the training/recovery balance right) I'll see some good improvements in the near future. But more data points are certainly required.

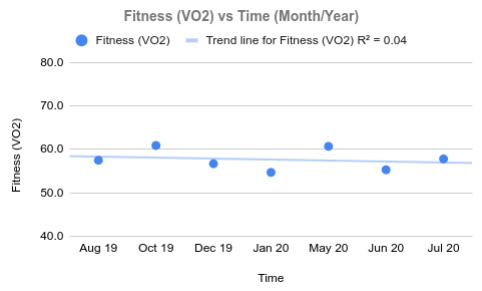

What about improvement over time? When I started riding three years ago my fitness level was very low, so there was a lot of scope for improvement, and I certainly saw huge gains over the first twelve months or so. Considering the low starting point, this would probably have happened almost no matter what kind of riding I did. But since I wasn't training with power during that time, I can't include this in my analysis.

But over the last year that I've had my power meter there's been no obvious relationship between my fitness and time, so it seems that I'm at a point where if I want to see significant further improvement, I've got to pay attention to the details of my training. Just guessing what's best won't work anymore: I need to put together a series of specific, focused and consistent blocks with a test at the end of each one, modifying my training based on the results.

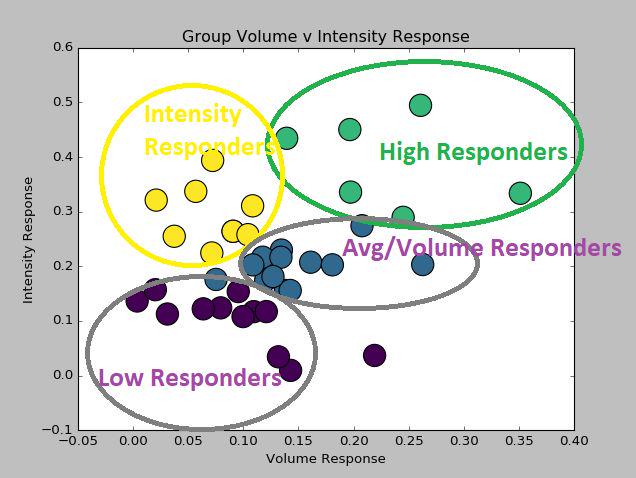

Here's a figure from the article, showing how athletes group by type:

The guys who win everything are in the green group, most people are in the blue group, and we all know a few purples!

It appears that I'm in the yellow group (actually, off the top of the scale). Unfortunately, until recently, I spent most of my time training like a volume responder; I nearly killed myself for much of 2019 repeatedly stringing together 20-hour weeks, during which time I seemed to get slower and slower, although this was probably down to exhaustion.

In fact, the likely explanation for the total lack of correlation between volume and fitness for me is that any gains from extra volume were offset by fatigue. If I'd taken time out for recovery when I was in the high volume period last year things might have looked a little better. Indeed, this year I've done just that, recording my best performances across the board in the last few weeks.

This analysis has reinforced what I've increasingly been suspecting: that I need to focus on riding harder, not longer. But intensity isn't a monolithic entity, so I'll need to go into even finer detail. I'm going to be keeping the volume relatively low for a while (averaging around 12 hours per week for the next couple of blocks), while I focus on intensifying my training. But there are several ways I could do this.

If I want to bring my average intensity for a block up to 65 TSS/hour, I could just do a lot of tempo rides (riding at 80% FTP), or I could do a combination of endurance rides and threshold and/or VO2 sessions, or just do a mixture of fairly short base training rides and very hard anaerobic sessions. And these will all have different physiological effects.

The first option is out, as I want a combination of easy and hard rides, not a lot of moderate ones. So it's mostly a question of getting the right balance between work above and below VO2 capacity, within the right proportion of hard and easy days. It's time to experiment, and, as ever, I'll be posting updates on how things are going over on my Training Notes page.

If you've got your own power and heart rate data, and you perform regular maximal long efforts of at least 20 minutes, then you've also got the information you need to do this analysis1. I think it would be well worth your while; maybe it'll lead you to a new way of training that works better for you.

1 You can calculate TSS scores and training hours using the Strava plugin intervals.icu (as I discuss here). Get the numbers and plug them into a spreadsheet.